It took director Jennie Livingston several years to complete her debut film, the great 1991 documentary of the underground 80s New York City drag scene and its ball culture, Paris Is Burning. That timeline makes sense given Livingston’s level of care and attention to detail, as well as the difficulties of funding and finalizing such a controversial project. Touching upon the black/latino gay & transgender community is a huge undertaking in itself; developing a narrative for mainstream consumption couldn’t be anything but challenging.

In documenting ball culture, Livingston gives her subject matter the room it needs to address the details of this specific environment, but she peers just long enough to respect its boundaries. It’s a direct piece of work, reflecting on the participant’s lifestyle with little to no fanfare, no ambiguity. It’s a blunt mix of glamour and dirt and style and sweat. You can easily imagine being cramped up in those tiny NYC apartments in the middle of the summer, but you’d be too busy hanging onto every word coming out of Pepper LaBeija’s mouth to notice.

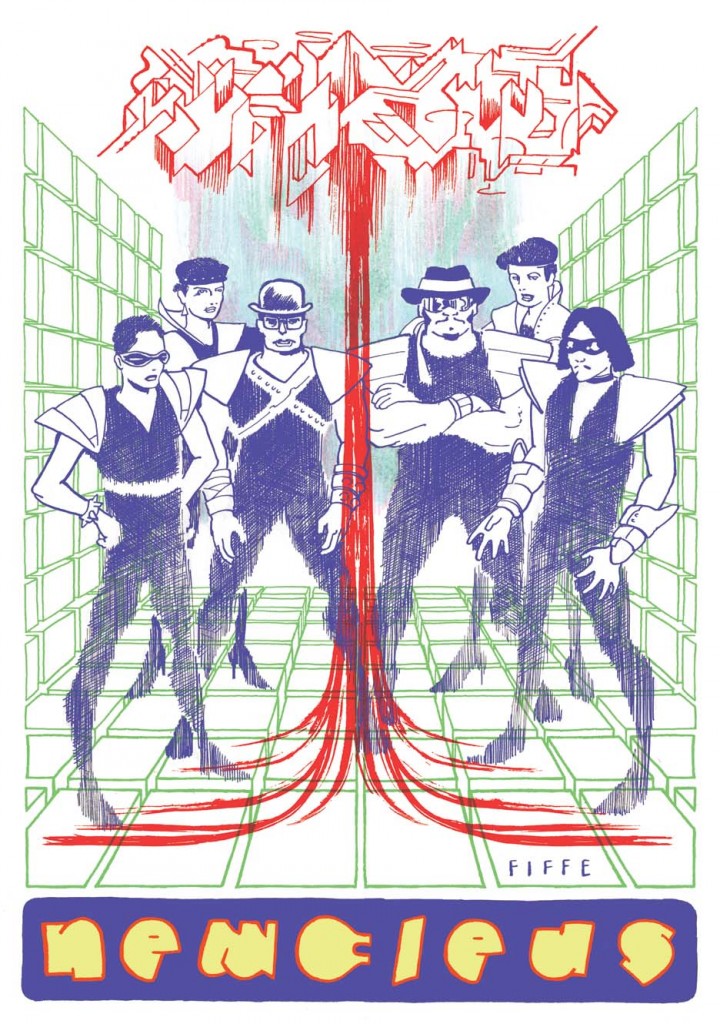

In a move that will surprise no one, I drew correlations between ball culture and the comics scene I deal with. It wasn’t my intention to do that – I enjoyed the movie on levels that have nothing to do with comics – but I noticed a couple of faint philosophical approaches that can be applied to our clubhouse. It’s a testament to the small group pulling together in order to move forward. That’s the Hallmark version of it but it doesn’t make it any less accurate.

Plus, any movie that starts with Noel’s freestyle classic Silent Morning automatically wins.

The film opens up with a father’s admonishment, “You have three strikes against you in this world… You’re black and you’re male and you’re gay. You’re going to have a hard fucking time. If you’re going to do this, you’re going to have to be stronger than you’ve ever imagined.” Paris Is Burning isn’t a mere portrayal of New York City drag in the 80s, that’s the obvious byline and it’s almost cheap to describe it as such. The real story is about being part of a subculture within a subculture. Despite or maybe in response to those three strikes (and other express concerns such as poverty and AIDS), this community developed its own nurturing, albeit competitive, social pool.

Gender roles and sexual identity operate as more than expression. It aims to reach for truth through an outside role. I don’t assume to know anybody’s motivation, nor do I want to describe it in blanket terms, but the members of this community do whatever they must to feel comfortable in their own skin, sometimes within roles that aren’t easy to hide, roles that shouldn’t be hidden to begin with.

The issue gets more complicated when you take gender identity issues and factor in the class rule of the times. Reaganomics didn’t cultivate an atmosphere that was kind to the poor, and although the glitz and the grime mingled in select club scenes, class crossovers were transient affairs. Fortune was not the domain of minorities, which makes the individual dreams expressed in Paris more fantastical than one would normally imagine. Whether it was dreams of fame or living a “regular” family life, they were always tempered with the more immediate thrill of shining at the ball. Dorian Corey put it best, “No magazine is gonna run up a cover of me if I go to a premiere. But it’s still a fame. It’s a small fame, but you absorb it, you take it, and you like it.”

Small fame is a version of something that’s just a placeholder for what we all want on a primal level, to be loved and accepted and recognized, and it may be too much to ask for. We may feed that longing for acceptance with cheap, empty dosages of pretend interaction, but it’s only because we need to feel something. If you press the issue, you’ll discover that Big Time Fame calls out to the worst in people, making them do deplorable things in the name of something that promises to love them back. As for people in the moment, though, like me writing this and you reading it, we look to reward ourselves by way of looking for proof that we are indeed loved. I’m still not quite sure if that’s an ugly thing or not.

Fame, how can something that has been cheapened still have so much power, and yet it never really meant anything?

Waiting to be famous is one of the subtexts in Paris, which in some regards isn’t unlike the Decline of the Western Civilization Part 2: The Metal Years directed by Penelope Spheeris. As far as movies that should be in print, you cannot find one more deserving that Decline 2. I clearly remember almost every featured band was shamelessly upfront about wanting nothing more than fame. The heartbreaking thing about Decline 2 is that you saw these future failures being unreasonably confident and sure that their success was simply a matter of time. Believing in yourself is one thing, but buying your own bullshit to the point where it’s probably masking some deeper damage is the stuff of sociopaths. There is something weird and sad about looking back knowing those bands’ trajectory, how they never made it within their own genre, and how that genre itself barely made it at all (Spheeris brilliantly ended the movie with a live Megadeth performance, perhaps as her final contrarian statement on the matter). That bulletproof certainty can cripple the people without the ability to call themselves out on their ridiculousness, and that’s the difference between those metal bands and the queens from 80s New York City.

Those attending the ball knew where they stood, as shaky a position as that was, and that small corner meant the world to them. It was a corner that went through many changes in a small amount of time, the way a vibrant and dangerous neighborhood makes room for a safer, richer citizen.

The spirit of that corner changes as it could no longer addresses the same concerns. But the fact that even the purest and most exciting of scenes will evolve into something arguably less magical makes it that much more special. It’s a thing that happens in the moment, and it’s usually gone by the time you notice it.

Those that make up the small world of comics may get genuinely excited about projects and creators and events, but it doesn’t come free from its own set of nonsense. Every art form has its fair share of problems, but I think comics are too small to survive this continued assault on ethical concerns, a treacherous value system, and a steady supply of self promotional delusion. This can be summarized as baby drama, especially if you throw in petty backbiting, but it still messes with our enthusiasm and stunts our growth.

It is the last thing I want to do, to compare 80s gay minority conflict to the troubles in comics, but the immediate connections I made were that both of our tiny worlds are made up of fragile egos driving an art form that’s punctuated by blips of innovation. I sensed joy and achievement in witnessing those ball competitions, especially knowing that poor kids had assembled gowns out of scraps just to shine for a night. Cartoonists want to shine in that spotlight as much as the next, but it stings when that spotlight is considered useless by the majority of those inhabiting that same small world.

It’s possible that we’re just desperately grappling onto something that’s shrinking, something that promises little more than diminishing returns. How can we expect our very own corner of the world to nurture us in economical and artistic ways when it clearly isn’t built to do so?

Therefore, all we’re left with is our own relationship to the medium. We have to dig deeper and find out what our little corner means to us on a personal level, outside of baby drama, outside of small fame. We can’t put any stock into those things that suck our enthusiasm dry. We have to ask ourselves what the point of all of this is, and then have the courage to be honest with the answers we come up with. We may not like them, but our survival as participants in this unequivocally complex medium rests on it.

Paris Is Burning, it’s a beautiful and brutal film. I can’t stop thinking about it. I would’ve been fine watching it once and tallying it as a movie I liked, but it wasn’t built for such passive treatment. It speaks to a larger thing that’s made more potent in context of the underdog.

“I always had hopes of being a big star. As you get older you aim a little lower and say oh, well, you still might make an impression. Then you think [you’ll leave] a mark on the world if you just get through it, and if a few people remember your name then you left a mark. You don’t have to bend the whole world. I think it’s better to just enjoy it, pay your dues. If you shoot an arrow and it goes real high… hooray for you.” –Dorian Corey