I binged. (TEEN TITANS Part One)

I purged. (TEEN TITANS Part Two)

I found the value of “archaeological” writing. (JSA/ALL-STAR SQUADRON)

I examined two unsung professionals. (JUSTICE LEAGUE of AMERICA)

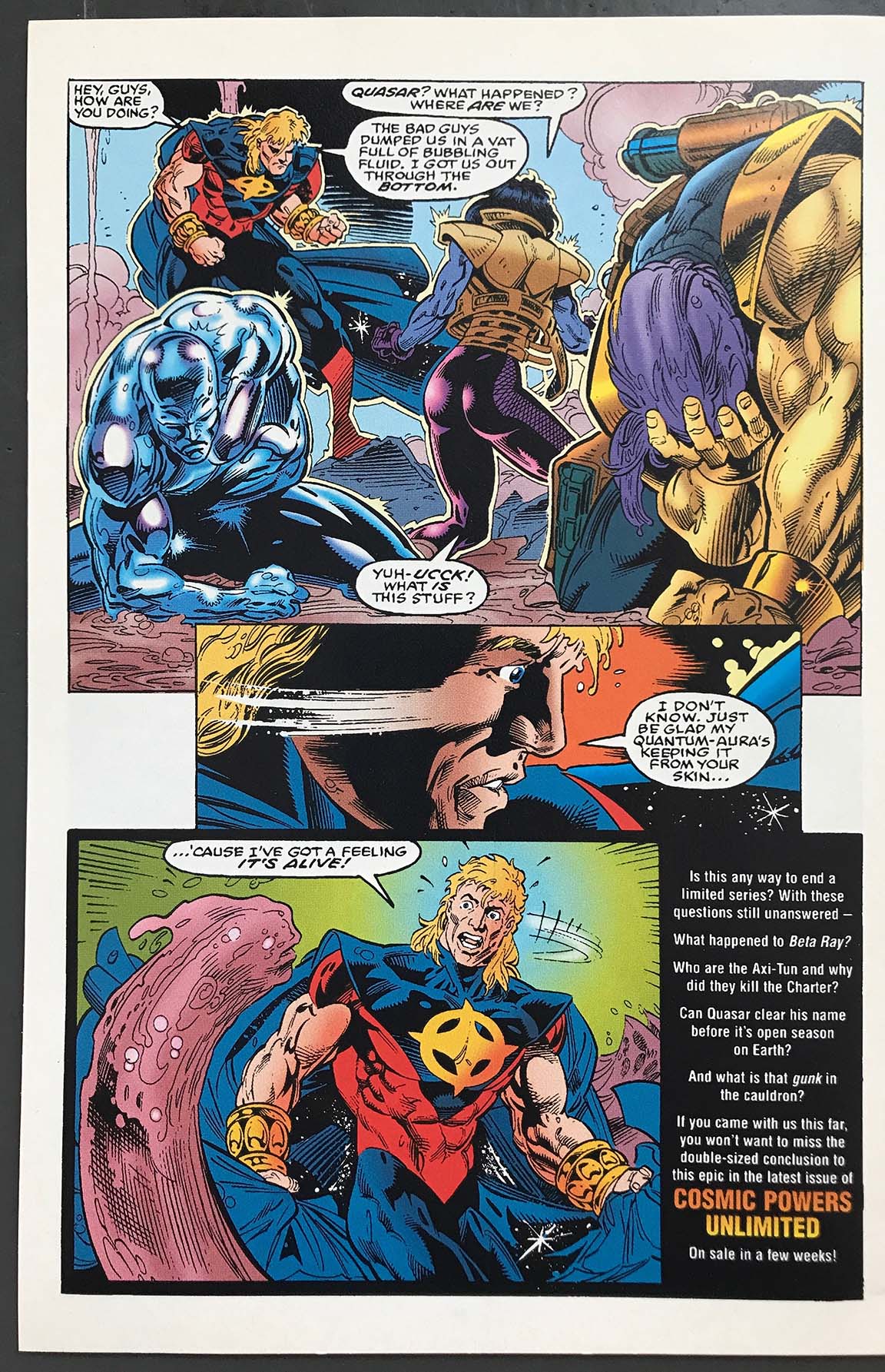

I followed the trajectory of one man’s obsession. (QUASAR & SQUADRON SUPREME)

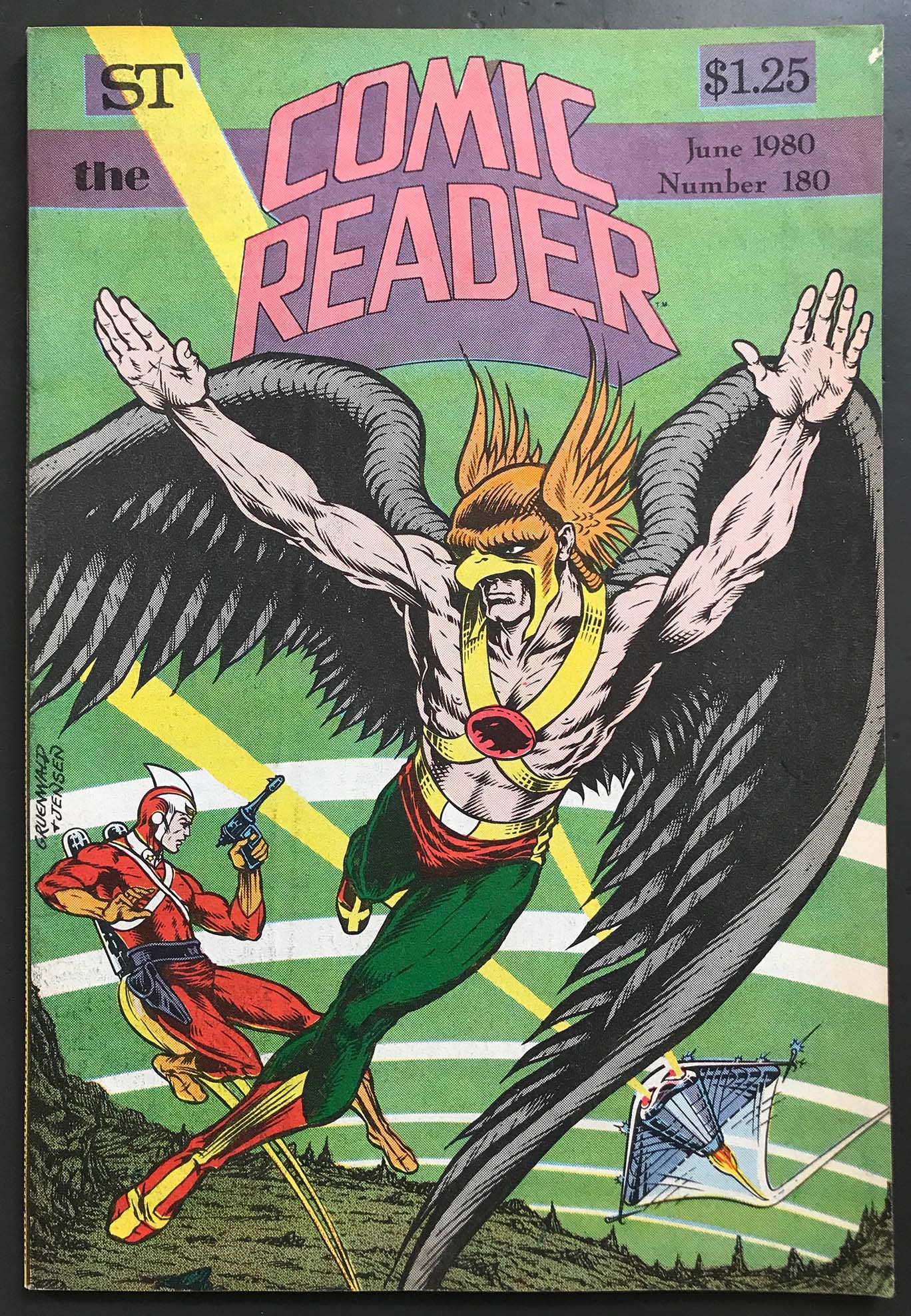

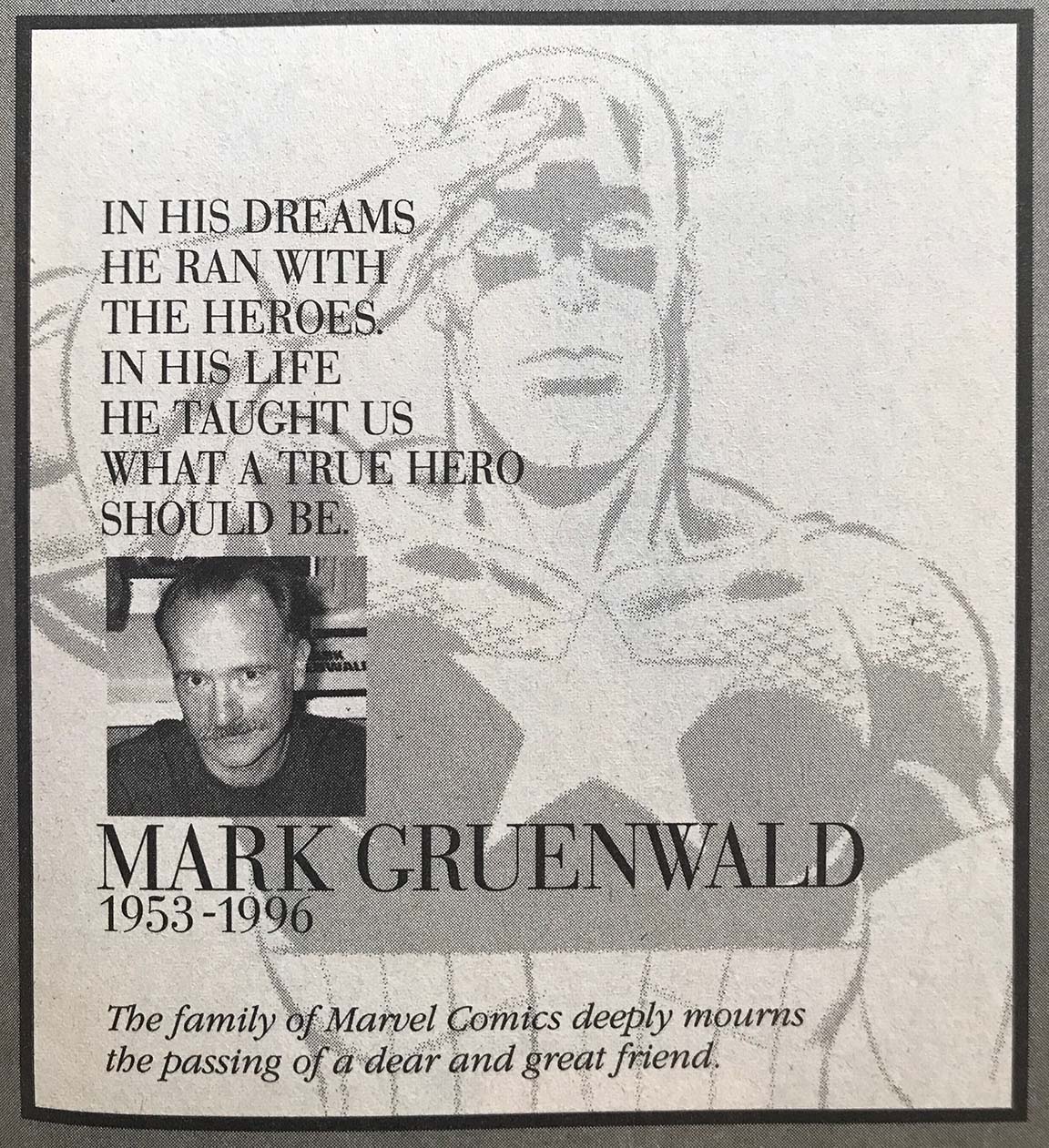

That man is Mark Gruenwald. I started this string of essays in order to work out my own interests, to capture my consumption in more or less real time and learn from it. It’s not that much of a coincidence that my initial desire for colorful superheroes at the beginning of this OVERWORD venture looped back to Mark Gruenwald’s work. In COPRA #30, May ’17, I dedicated a large portion of my comic’s letters page to some thoughts on Gruenwald’s approach to writing. I loved it, warts and all, but I didn’t crack the code. A simple, surface-level appreciation, a good excuse to draw little portraits.

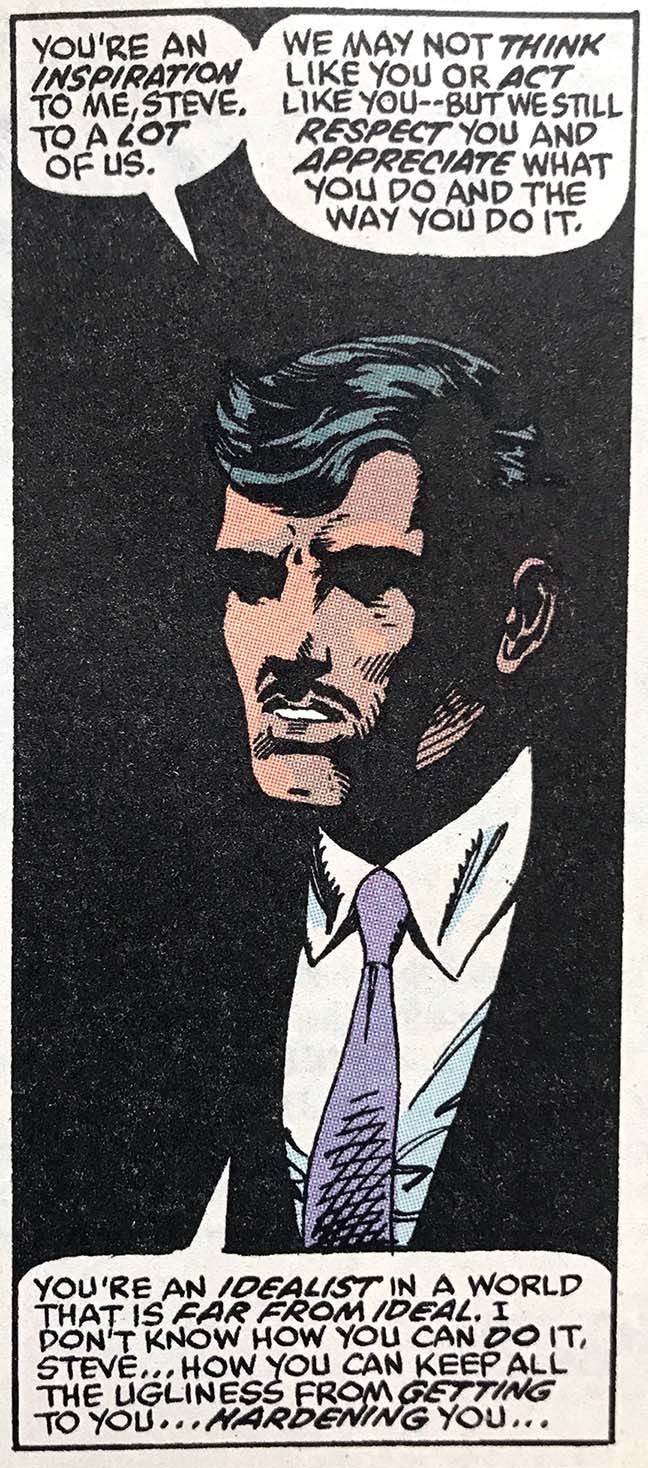

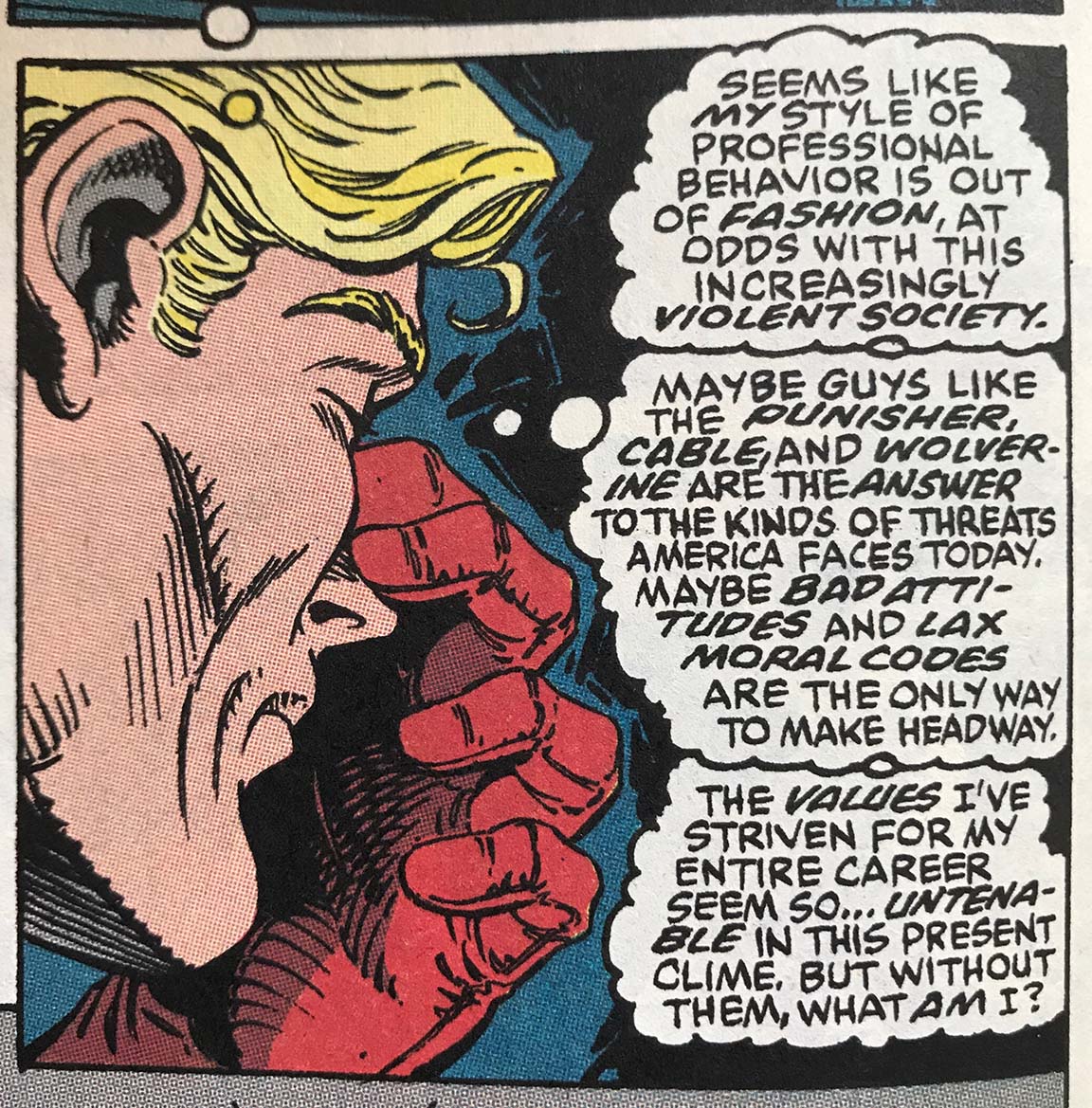

In short, clarity, continuity, and commitment are the tenets to abide by. Be clear in the ideas you present, respect the foundation you’ve been given permission to build on, and see your ideas through no matter what. There’s a ritual in all of that, a built-in way to organize and communicate. It’s a positive, healthy approach to working within a larger structure; in Gruenwald’s case, the Marvel Universe. (I still highly recommend his Mark’s Remarks column from Marvel Age #89, June1990, for a borderline cruel self-assessment.)

This and all CAP panels are from #401, June 1992.

We’ve reached peak clusterfuck in terms of any sort of hardline continuity in comics today. There’s a thin narrative thread running through mainstream comics, but we all know it doesn’t matter anymore. Anything goes, it just has to be compelling, it just has to sell books, and so the hyper attention to long running, company-wide continuity doesn’t hold much weight anymore.

When was the last time it did, though? Crisis in ’85? Post-Heroes Reborn? Pre-Hickman’s Secret Wars? Like Roy Thomas a generation before him, Gruenwald lived to serve continuity. There was a groundwork for him to study and work from, and it had real value to the readers, too. That was part of the Marvel appeal, being the longest running shared universe in history.

So I can’t help but root for the guy who was fighting an uphill battle with the times. Especially when his writing style was geared towards those unwavering convictions. And he wasn’t gonna go rogue and do his own thing! No way was he gonna go independent; as established in the Quasar post, the Big Two establishments are where it’s at. Anything outside of that simply didn’t count. And this isn’t some sort of demented corporate loyalty, it’s a marriage to the ideas he surrendered to as a kid, as a professional, and as a creative force.

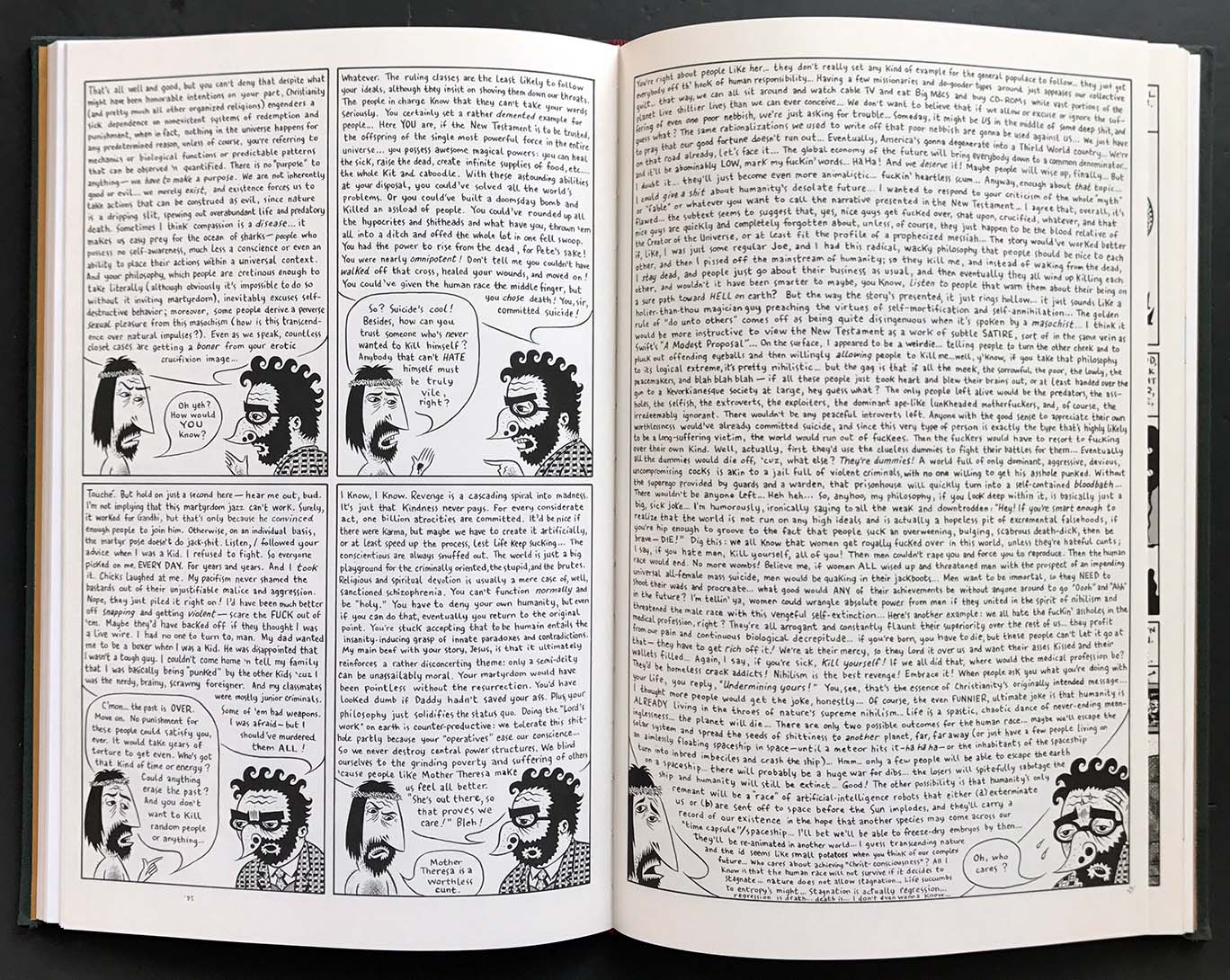

I wanted to talk about uncool things: footnotes, thought balloons, exposition, forced flashback sequences/recap pages, all of it. I wanted to point out that reading text-heavy superhero comics is not unlike reading a Chris Ware comic, where stories are sometimes driven by ever-changing memories and experiences and they might even carry some personal insight. In terms of the word balloon as a weapon, I also wanted to draw a correlation between Gruenwald’s coded personal frustrations and Ivan Brunnetti’s Schizo.

I even wanted to touch upon Manga and how it traffics in mid-punch interior monologues, but how literalism has won in American comics. How starting with the art of Neal Adams and continuing with Alex Ross, from Stan Lee to Moore to Bendis, “realism” has always been rewarded in superhero comics. How a Chaykin script is not a casual, brisk affair and how Windor-Smith’s Weapon X script succeeded through sheer novelty and how the Sin City movie proved you can’t just recite a comic book script because it’s meant to be read… silently. (Which is precisely why I deeply loathe live comic book readings. A sadder misuse of everyone’s time I have yet to come across). I also wanted to get deeper into how I now see Ditko’s didactic political comics, because his goal wasn’t to make you kill some time on fluff, but rather to communicate no matter what. We read his hieroglyphs. We read his words. We read his maps. Everything is a map.

A rare Gruenwald/Ditko collaboration from Daredevil #234, Sept. 1986.

I wanted to write about all those things in great detail, really build a case for overwriting and why it doesn’t deserve the bad rap it has. I wanted to convince you of something – Mark Gruenwald’s greatness – but I didn’t want to drown you in adjacent ideas. I’m now less compelled to convince anyone of anything as I realize this has been a naked conversation with myself. Me, trying to figure out this slice of comics process in public and what it means to me personally. All of these words being read or not being read, they’re right here for me to try to express something, to document the things that mean a lot to me. Mark Gruenwald, his work means a lot… but why? Why do I cling to this adoration? Is it healthy, is it masking something? I’m not ready to read into the pattern of me falling under the spells cast by creators long gone: Jack Kirby, Jim Aparo, Archie Goodwin, Steve Gerber, Dwayne McDuffie… Is that my coping mechanism? Is this how my grief and anxiety have manifested themselves?

That last Quasar post was what did me in. We all like a good comeback story, but Quasar went down barely swinging. I’m humbled by the sheer amount of effort that went into making something that had a fate worse than the dollar bin awaiting it — it has a legacy of mockery. That breaks my heart. Something about that one stung, probably because it seemed like the one that meant the most to Gruenwald. I’m not saying everyone deserves a cookie for merely trying, but Quasar the book had a lot of soul, and except for the Avengers: Infinity mini-series written by the great Roger Stern (and dedicated to Gruenwald), no one has written Quasar the character with the same level of agency or integrity since.

Maybe it’s because I work in solitude and I’m left to wallow in my own thoughts and feelings for long stretches of time. I dwell on things I perhaps shouldn’t dwell on. Analytical to a fault. I use Gruenwald as an example of how to march forward, how to keep your spirit strong. So I keep things moving, I keep things healthy and positive.

I can also relate to Gruenwald, which is probably why I’ve attached myself to his body of work so aggressively. I can relate to his diligence, his work ethic, his intensity. But in the end, you ask, exposition fetish and sentimentality aside, is the work any good? Of course it is. I wouldn’t have gotten this far into the deep end if I didn’t think so. Gruenwald’s stories draw me in, his words are very comforting to me, his explanations are soothing; anyone else doing the same is highly irritable. (Trust me, I’ve tried other brands of continuity cops.) I might have been slightly thrown off by Gruenwald’s underwhelming final Captain America issue, but knowing now how Quasar ran its course a year prior, I can see why there was no energy left to channel. All things end, but unpopular things end quicker.

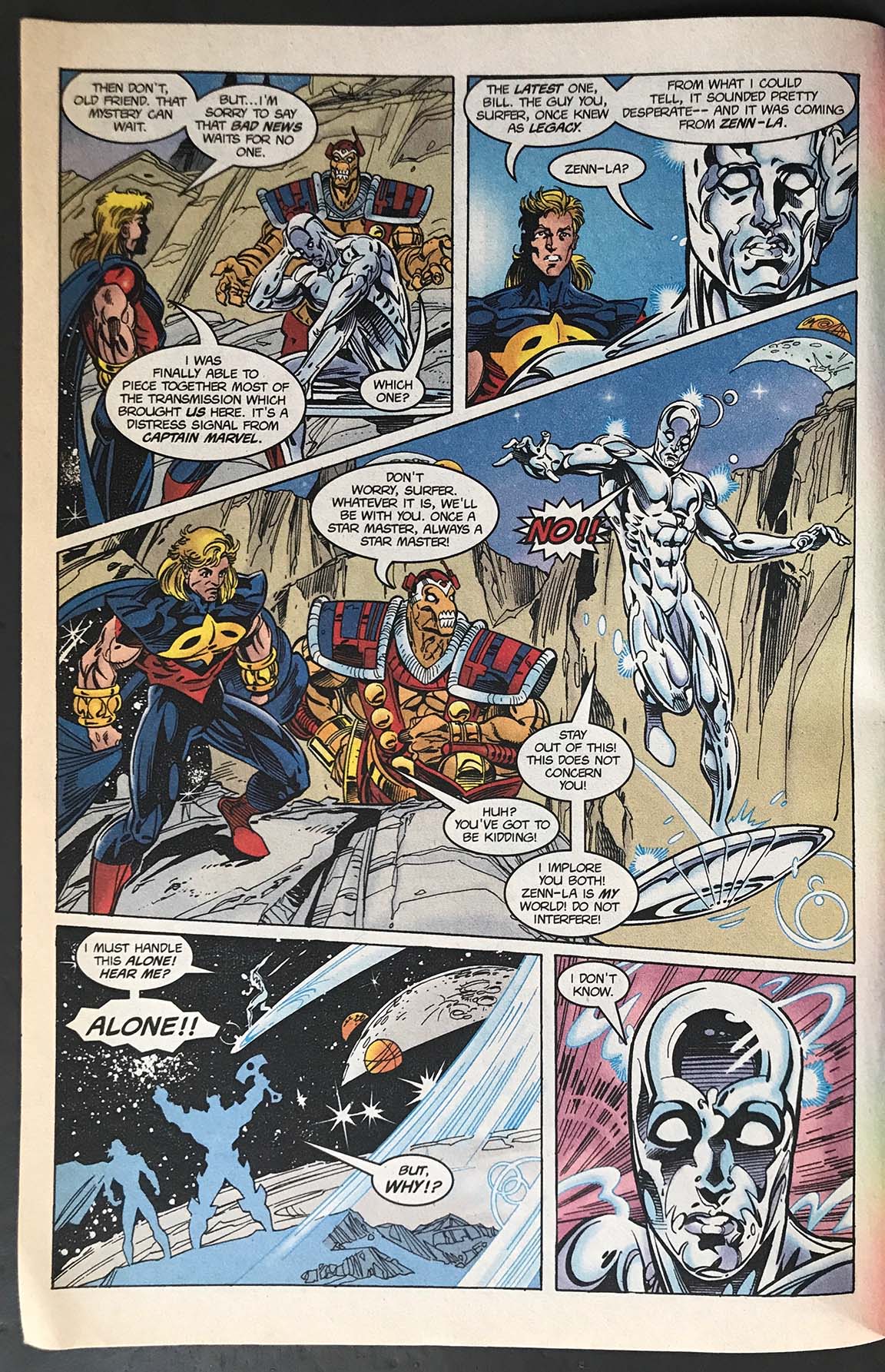

Starmasters #3, Feb. 1996, was the last time Mark Gruenwald wrote Quasar.

Silver Surfer #122, Nov. 1996, was the last time Mark Gruenwald edited Quasar.

From Silver Surfer #122:

Picture this: waiting for one comic book, say… Captain America. You get one issue a month. And your local vendor might not get consecutive issues in a row. The comics were written with that in mind, with refreshers and updates, with callbacks to older tales to build a mythology and get you buying back issues. Discovery was key, and imagination acted differently, it was stoked by necessity. Nowadays, our imagination has morphed into something that has expectations, it requires immediate content and consumes it quickly. There’s no time to wait, no patience, things are moving forever fast. That’s why old collections of old comics are unreadable: they were not written for us, they were for the reader longing for that next issue back in the day. (Though, I did really enjoy The Project Pegasus Saga when I read it in its entirety during my recent Quasar binge.)

Being forced to wait, letting the information that you do have build in your head sparks the imagination, it shapes and heightens the experience. Dan Clowes once referred to old movie stills in monster magazines as having more impact than when you eventually watch the actual movie. Having half the picture is a richer experience than when it’s laid out.

And yet despite the value of a half-full picture, there Mark Gruenwald was, explaining and showing off his knowledge, well earned through years of dedication. It was his job to keep track of continuity so you didn’t have to, so you could sit back and enjoy. Plus, let’s give the man his propers: he was a killer writer. His was a gift brighter than any colorful superhero I’ve been clamoring for. And yeah, I still believe Gruenwald has more in common with Brunetti than he does with someone like Tom DeFalco or Kurt Busiek. It’s not just exposition, it’s not just trivia rambled by know-it-alls, it’s transcendent passion at work. It’s a painful urge to get the words out no matter what, as many words as it takes because words are all you’ve got and somewhere, someone out there will read them and they will understand.

It took me forever to understand, but the words took hold, they landed. The words made my life better.

Michel Fiffe, June 2018